Blind Faith, Port Hope and Public Charity for a

Corporate Citizen: The Nuclear History of Port Hope, Ontario

Since

the 1940s, nuclear weapons tests, power plant failures and uranium mining have left

radioactive contamination at hundreds of sites around the world. Whether the

contamination is from weapons tests, accidents, or just reckless routine

operations, the story of the affected people unfolds in much the same way, as

if it were a formulaic plot for a generic television soap opera. Communities

that have been chemically contaminated follow much the same script, but

radiation adds some distinctive elements to the situation.

Radiation

is invisible, and it has always been imbued with a diverse range of magical

powers in science fiction. Ironically, in a very real sense,

radiation does make people invisible (the phenomenon is fully explained by

Robert Jacobs in Radiation

Makes People Invisible)[1].

Once groups of people have become victims of a radiological contamination, they

are, in addition to being poisoned, marginalized and forgotten. Their

traditions and communities are fragmented, and they are shamed into concealing

their trauma. When contamination occurs, there is a strong impulse even among many

victims to not admit that they have been harmed, for they know the fate that

awaits them if they do.

The

victims are helped in this denial by those who inflicted the damage on them because nuclear

technology, both for weapons and electricity production, has always been

treated as two sides of a single national security problem that requires secrecy and the

occasional sacrifice. Its workings must be hidden

from enemies, terrorists and citizens themselves. Thus governments have never

been interested in helping their citizens investigate nuclear accidents and

environmental damage left in the wake of nuclear development.

As

secretive programs of nation states, nuclear complexes operate free of any

governing body that could provide checks and balances. In this sense, they are

a more intractable problem than the corporate villains that are occasionally

held in check by government supervision. The American tobacco industry was

eventually forced into retreat by government, and it had to pay enormous

damages to state governments for health care costs, but the nuclear weapons and

energy complexes still operate free of any higher power that could restrain or

abolish them.

Thus

it is that hibakusha (the Japanese

word for radiation victims) become invisible. When a new group of people become

victims, such as in Fukushima in 2011, they feel that they have experienced unique

new kind of horror. For them, for their generation, it is new, but for those

who know the historical record, it is a familiar replay of an old story. The

people of Fukushima should know by now that they are bit players who have been

handed down a tattered script from the past.

A

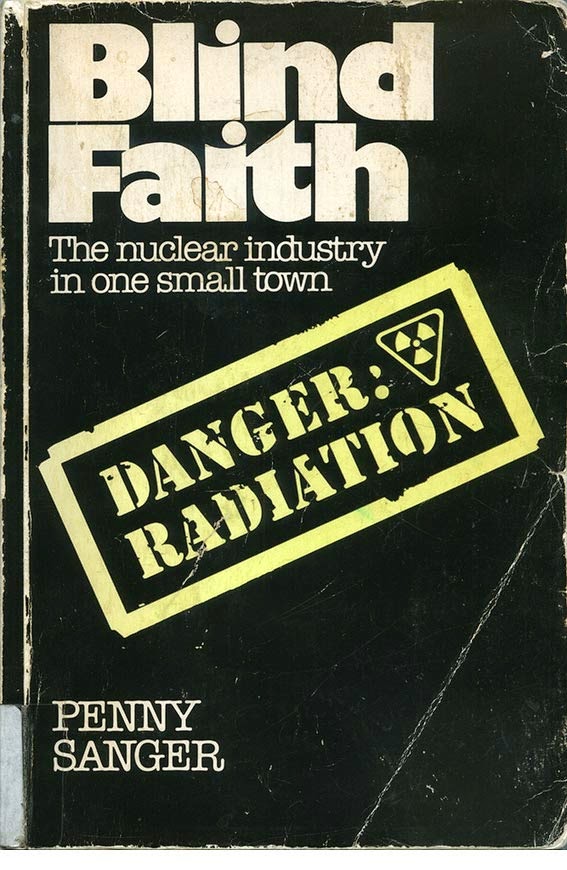

case in point is Blind Faith, the superb

1981 book by journalist Penny Sanger, about the small irradiated Canadian town of

Port Hope on the shores of Lake Ontario. (See the timeline at the end of this

article)[2] In the 1970s it faced (and more often failed to face) the toxic legacy

of processing first radium, then uranium for nuclear weapons and nuclear power

plants. In a saner world this book would not be out of print and forgotten. It

would be a classic text known by everyone who has ever had to share his town

with a dangerous corporate citizen. Then there would be no surprises when a

nuclear reactor explodes or a cancer cluster appears somewhere new. It wouldn’t

be a shock to see the victims themselves fall over each other in a rush to

excuse their abuser, beg for a continuation of jobs and tax revenue, and

threaten the minority who try to break the conspiracy of silence.

Blind Faith is available on a website

dedicated to the history of Port Hope. Since it is out of print and over

thirty years old, I asked the author if she would allow its free distribution as a pdf file. She gave her permission, but of course the common sense

rules apply. If you want to sell the book, ask the author for permission. If

you redistribute it free, in whole or in part, do so with proper citation.

Read

it in a web browser:

Free

download (permitted by author):

Penny

Sanger, Blind Faith (pdf) (McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1981), 135 pages.

|

On

the back cover of the 1981 paperback edition of Blind Faith there was an endorsement by the late great Canadian

writer Farley Mowat, who passed away in the spring of 2014:

Penny Sanger has written a fascinating and fearsome

account of the emotional turmoil that engulfs a small town when it discovers

that its major industry is a threat to the health of its citizens. This is a

classic account of how economic power enables industry to ride roughshod over

those who must depend on it for their daily bread.

Although

I wrote above that Blind Faith

illustrates universal truths about what happens to communities contaminated

with radiation, there are always unique aspects of the situation that come into

play. In this case, we see the extreme complacency and obliviousness of

Canadian society to the role that the country played in the development of

nuclear weapons and nuclear power. The uranium refinery in Port Hope was a key

element in the Manhattan Project. It was the main facility for refining uranium

ores from the Congo and northern Canada. However, as a subordinate nation in

the American-led war, Canada just had to go along in complete secrecy. As was

the case even in the US, there was never any debate in public or in elected

legislatures. Canada was just taking orders and didn’t have to feel

responsible. Canadians are still largely ignorant about their complicity in

making the bombs that fell on Japan, as they are about being one of the sources

of the uranium that was in the reactors of Fukushima Daiichi.

Another

factor in our sense of irresponsibility is the comfortable delusion that all

bad things are done by the evil empire south of the border. We’re the good

guys, with universal health care and multiculturalism.

The

Port Hope refinery began operations in the 1930s to produce radium from uranium

ore. The ore came from the recently discovered rich deposits in the Port Radium

mine on the shore of Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories. This mine

would later become one of the primary sources of uranium for the first atomic

weapons, but in the 1930s radium was the only product that had value for its

use in making luminescent paint and medical applications.

By

the 1930s it was well understood that radium and uranium mines were extremely

dangerous. The high lung cancer rates of miners in Czechoslovakia had been

noted for a long time, but there were others who failed to acknowledge any

connection. Marie Curie died in 1934 from aplastic anemia, and she never

acknowledged that her numerous health problems had been related to the vials of

radium that she carried around in her pocket or perhaps to the unshielded x-ray

machines she worked with.[3] Today her diaries and papers still have to be

stored in a lead box.

Because

there was no consensus on the dangers of radium by the early pioneers (DNA wasn’t

even understood until the 1950s), there were few safety controls in place when

radium became an industrial product. Radium paint workers got sick and died for

mysterious reasons, as did workers in processing plants like the Eldorado

Mining and Refining facility in Port Hope. Almost nothing was done to protect

workers or properly dispose of the waste product. The wastes were isolated in a

dump, but when that became problem, the dirt was sold as fill to unsuspecting

(or unscrupulous) buyers and used at construction sites all over town.

It

wasn’t until the 1970s that a few citizens of Port Hope started to notice

radioactive wastes turning up in various locations. This new awareness was the

beginning of bitter social divides that would be familiar to anyone who has

followed what has happened in Fukushima prefecture since 2011. The enormous

implications of the necessary cleanup forced political and economic powers to

downplay or ignore the dangers, and ostracize anyone who dared to threaten real

estate values and tarnish the image of the community. The mayor even boasted of

what a great role the town had played in the Cold War by refining uranium so

that America could beat back the Soviet threat, as if the contamination had

been worth it.

There

was a minimal recognition of the need to do something about the worst hot

spots, to placate critics and relocate residents in the worst danger. Everyone

agreed, for example, that something had to be done to clean up a contaminated school, but for the most part

the problem was denied in favor of keeping the town’s biggest tax payer and

employer satisfied. At the same time, the federal government was not motivated

to do anything that would set back the expansion of the nation’s nuclear energy

program. The Darlington and Pickering nuclear plants were built nearby in this

era on the shores of Lake Ontario.

By

this time, Eldorado was no longer selling uranium for American nuclear weapons,

but it had become a major player in the uranium fuel market. It would provide

the fuel for the large fleet of CANDU reactors that Ontario was building, and

by the 1980s Eldorado was privatized, turned into Cameco, and was then selling

about 80% of its output to the US where the uranium was enriched for use in

light water reactors. Thus a full acknowledgment of the extent of the problem—the

cost of cleanup and the health impacts—would have jeopardized the refinery’s

role as a major supplier in a growing nuclear energy industry. Eldorado might

have seemed like a wealthy giant to outsiders, but the uranium business was

perilous and changing rapidly. Just as the public was becoming aware of the extent

of the pollution, Eldorado was stuck in long-term contracts that were a bargain

for its customers but disastrous in a time of soaring costs.

The

situation presented especially difficult obstacles for opponents because

Eldorado was a crown (publicly owned) corporation. One obstacle was secrecy. Since

1942, the operations of Eldorado have been state secrets, and much remains

locked up in archives that are yet to be opened to historians.[4]

The

other problem was in the fact that the government had no interest in investigating

its own corporation, and because Eldorado was a federal crown corporation, the

province of Ontario had no authority to investigate it for environmental crimes.

Thus complaints from citizens ran into this dead end.

Similar

situations in the United States, such as at the Rocky Flats plutonium pit factory,

involved the Department of Energy hiring large defense contractors like

Rockwell to manage the plant. This meant there was a possibility the

Environmental Protection Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigations could

act if enough public pressure were applied and evidence of crimes became

apparent. As much as the American nuclear weapons complex was a monstrous crime

against nature, there is at least something redeeming in the fact that the

American system of government consisted of various institutions that could sometimes

keep the others in check. In the dying days of operations at Rocky Flats in 1989,

the EPA and the FBI raided the facility which was then operated by Rockwell

under contract for the Department of Energy. The US government essentially

raided and prosecuted itself.[5] Unfortunately, no such checks and balances

existed in Canada’s nuclear industry. The federal government and its crown

corporation had a monolithic grip on the historical records and on decisions

about environmental safety and health related to radiation. There was no

outside force that had legal authority to prosecute them and force them to

divulge information.

There

are some further details in Blind Faith

that stand out in my memory. They are unique to the Port Hope story, but also typical

of stories of other irradiated and poisoned communities.

At

one point, a doctor in a nearby town grew alarmed at the number cancer cases

that appeared in his patients from Port Hope. He tried to bring the issue to

the attention of health authorities, but was slandered and opposed by city

officials to a degree that he found alarming. He had foolishly thought that his

efforts to speak up for public health would be appreciated. Instead, city

officials made a pathetic attempt to sue him for defaming Port Hope, and when

that immediately failed, they complained to the provincial medical association.

They had thought that this would succeed in getting him stripped of his license

to practice, but they were quickly rebuffed by the medical association that

found no fault in a doctor expressing his opinion about a serious public

health concern. Such was the sophistication of the strategies of the town

fathers as they floundered for ways to preserve the tax base.

Eldorado

and the federal government, and even the Workmen’s Compensation Board were

equally combative in the lawsuits that former workers eventually managed to

bring to court. Lung cancer was the only health issue that was admitted for

consideration in the lawsuits, and once it became a legal battle, all ethical

considerations went by the wayside. It became a matter of winning at all costs,

of admitting to absolutely no wrongdoing no matter how absurd the defendants

had to appear. The government lawyers played hardball, abandoning any thought

that the government corporation owed anything to the citizens who had lost

their health working on a project so essential for national security. The government

side was not too ashamed to engage in extreme forms of legalistic

hair-splitting. For example, the victims were forced to prove their exposure,

but everyone involved knew that the only party that had the information were

the defendants, and Eldorado did its best to conceal it. One victim was denied

compensation because the records showed his cumulative exposure was 10.8

working level months. Expert witnesses were brought in to say that the

threshold of danger to health was 12 working level months.

Another

segment of the book that stands out is that in which Penny Sanger was able to discover

that at one time, before the contamination was known by townspeople, the

Canadian military had used Port Hope as a training ground for operating in the

aftermath of nuclear warfare. The military knew what the citizens of the town

didn’t know at the time: there were sizzling hot spots of various sizes all

over town, so it made for an ideal training ground for soldiers who would have

to map radiation levels and move through contaminated terrain after a nuclear

attack. After the training exercise, they might have bothered to tell the

locals about what they were living with, but the contamination remained a

secret until residents started to figure it out for themselves.

As

the years of legal struggles and activism dragged on, there were signs that the

government was tacitly admitting to the scale of the problem, even if it

refused to accept legal responsibility for health damages. The management of

Eldorado was routed, and it would eventually be privatized and turned into

Cameco. The refinery became the object of pork barrel politics when the federal

Liberals came back to power in 1980. They announced that the more dangerous

uranium trioxide operation would be relocated to Blind River, a town in the

north that had voted Liberal. Eldorado wanted the refinery kept in place close

to markets. (I wonder if anyone saw the ironic symbolism of progress in the

names; going from hope to blind—a fiction writer couldn’t have

come up with anything better).

One

stand-out account is that of a widow whose husband, a long-time Eldorado

worker, had died of lung cancer at age 50. He had worked at Eldorado for over

twenty years, during the era when workplace monitoring and standards were

non-existent. Her husband was no longer there to say whether he too was “philosophical”

about it and “couldn’t be bitter about it” like his wife and his daughter

claimed. The widow said that in spite her husband’s shortened life, they were

grateful for the good jobs and university education that the children were able

to get. Thanks to Eldorado, they had come up in the world. Thanks to dad so

agreeably sacrificing the last thirty years of his life.

Penny Sanger

passed no judgment on this thinking, but I find it to be a rather nauseating

example of working man’s Stockholm syndrome. The victim has internalized the

values of the captor, and lost self-esteem and critical thinking skills in the

process. The bereaved family slumps over and shrugs pathetically that they “can’t

be bitter about it.” They’ve internalized the value that children have to go to

university to live worthwhile lives, and it’s alright if parents have to kill

themselves to accomplish this goal. If indeed going to university is so valuable,

it’s obvious that in Canada there have been other ways to get there.

It

seemed to never occur to any of the Port Hope boosters that there were dozens

of similar towns in rural Ontario that had found ways to survive without

hosting toxic industries. I know a family of Polish immigrants who landed in

Port Hope in the 1960s, and they managed to get by without working for Cameco.

The children had the sense to leave town after high school when they saw their

friends going straight to grim lives working with the yellowcake down at the

plant. One of them managed somehow to get a couple of university degrees after

he left town.

This

lack of imagination among the terminally hopeful applies more widely. Not only

do company towns fail to imagine less toxic ways to live, but large nations

also fail to imagine new paradigms for energy and economic systems. Perhaps the

widow’s tale is a metaphor for something bigger.

Port

Hope’s troubles with its radioactive legacy didn’t end with the privatization

of the refinery and other varied forms of resolution that came about in the

1980s. A cleanup was done in the 1980s, but twenty years later hot spots were

still turning up, and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission finally admitted

the extent of the problem and committed taxpayer funds to a billion-dollar

decontamination project which is presently underway—an amount that is,

ironically, about the same as the budget for the new Chernobyl sarcophagus

under construction now.[6][7]

There

is further irony in the fact that while the Fukushima and Chernobyl exclusion

zones have become the famous global icons of radiation-affected communities,

the Port Hope disaster has no place in Canada’s national consciousness.[8]

There is little public awareness of the history, and the present billion-dollar

decontamination project has received scant media attention and no public alarm

over the high cost. Meanwhile, opposition parties in Ontario have focused in

recent years on stoking citizen outrage over cancelled plans to build gas-powered

electric generating stations. That loss was comparatively little, amounting to

only a few hundred million dollars. The same can be said of the province’s plan

to spend $20 billion or more to refurbish nuclear power plants to operate them beyond

their originally planned expiry dates. This issue receives little attention, as

none of the major political parties wish to use it to stoke debate with rivals.

Nuclear energy has almost completely vanished from political discourse.

Meanwhile,

Cameco has continued to practice its philosophy of good corporate citizenship

by funneling all its uranium sales through Switzerland in order to avoid Canadian

taxes. The company is in an ongoing legal battle with Canada Revenue Agency, while

it has warned stockholders it may owe as much as $850 million in back taxes[9].

Note that this amount falls a bit short of the cost of the decontamination

project in Port Hope, but it would provide a big chunk of it.

Notes:

2. From The Toronto Star, April 2011:

1930s:

Crown corporation Eldorado Nuclear Ltd. begins refining radium, used for

treating cancer, and uranium that helps the Manhattan Project develop the first

atomic bombs.

1940s-1960s:

Low-level radioactive byproducts and other toxins from the plant enter the

environment through use of contaminated fill, and to some extent through sloppy

transport, and water and wind erosion in storage areas.

1970s:

New concerns prompt the Atomic Energy Control Board to scour the town in search

of hot spots. Cleanups are undertaken in dozens of locations.

1988:

Eldorado is sold to the private sector and becomes Cameco.

1990s:

Worried about health effects, citizens begin taking an active part in nuclear

license reviews of Cameco and ask the federal government to study the effects

of radioactive waste in the town.

2001:

Ottawa pledges $260 million for cleanup. An estimated 1.2 million cubic meters

of soil contaminated with low-level radioactive waste and industrial toxins

will be dug up and trucked to a new storage facility north of the town.

2002: A

federal study finds that death rates, including cancer deaths, are no higher in

Port Hope than elsewhere in Ontario.

2004:

Families Against Radioactive Exposure (FARE) is formed to counter Cameco's plan

to produce a more potent fuel known as enriched uranium. It demands an

environmental assessment of the proposal by a review panel, but the Canadian

Nuclear Safety Commission says a screening is sufficient.

2005:

Dr. Asaf Durakovic, research director of the Uranium Medical Research Center in

Washington, D.C., agrees to carry out a study of Port Hope residents for

evidence of illness resulting from exposure to radioactive materials.

2007:

The study finds small levels of radioactive elements in the urine of four of

the nine people tested, including a child younger than 14. More calls follow to

put the town under a health microscope.

2009: In

spring, the nuclear safety commission reiterates that no adverse health effects

have occurred in Port Hope, and that its cancer rates are comparable to other

Ontario towns.

2010: In

fall, the cleanup begins with a trial dig in a backyard.

November

2010: Acclaimed anti-nuclear activist Helen Caldicott calls the presence of

contamination in Port Hope “a disaster” and says the only solution is to

relocate the 16,000 residents.

2011: A

full-scale cleanup will begin later this year, lasting a decade and costing at

least $260 million. The final scope and price tag are unknown. [In early 2012,

the federal government announced that it was going to cost a little more: $1.28

billion! And it was being touted by local conservative member of parliament

Rick Norlock as a fantastic job creator.]

4. Peter

van Wyck, Highway of the Atom (McGill-Queen's

University Press, 2010). This author describes the obstacles still in place for

scholars wishing to access information in the archives about Canada’s nuclear

past.

5.

Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing

Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats (Broadway Books, 2012).

8. The situation

is the same in numerous places in many countries. For a sample, see the maps in

The Wall Street Journal series of

reports Waste

Lands. Every

country that has mined uranium or developed nuclear weapons and nuclear power

has a similar list of contaminated lands.