A

recent letter in The Japan Times

complained that opponents of nuclear power always conflate good nuclear power

(electricity) with bad nuclear power (bombs). This blog is guilty as charged,

and it’s a valid question to ask, but unfortunately, there are some very good

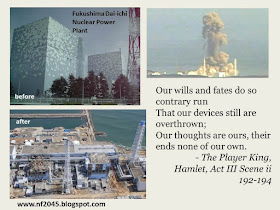

reasons why you can’t have your yin without your yang. Seriously, viewing the

photo above of the Fukushim Dai-ichi Unit 3 detonation, who wouldn’t be

terrified by both the civilian and military uses of nuclear energy?

To understand why the two co-exist

requires a look at the origins of nuclear energy. The history shows that during

the days of discovery, no one had the faintest thought of using nuclear fission

to boil water, even though it wasn’t too hard to imagine how the chain reaction

could be moderated. The history also shows that a vast, expensive

infrastructure for building weapons had to exist before nuclear power plants

were built – mostly as an afterthought justification for having made the

weapons complex.

Consider how hard it has been to get modern

civilization off its addiction to fossil fuels. There has been no

transformative, massive investment in renewable energy, and the likely reason

is that it has no potential for massively destructive weapons that would change

the balance of power in the world.

Imagine that the discovery of fission had

happened during peacetime. Instead of Einstein writing a letter to President

Roosevelt warning that the Germans might build a terrible new weapon, he would

have been asking for government subsidies for a new kind of energy that some

friends were trying to launch in a start-up company. He would have explained

that a multibillion-dollar infrastructure was needed to set up the mining,

processing and power stations. Massive fossil fuel-burning generating stations

would be needed to run the enrichment facilities. The outcome would be

uncertain, and the details worked out along the way. Oh, and by the way,

devastating military applications would be possible, but a system of global

surveillance could ensure that no nation ever submitted to the temptation to

make such a weapon. Furthermore, the used fuel would be the most toxic thing

ever known, and potentially a weapon of mass destruction. A way to dispose of

it would have to be worked out. Devastating accidents could happen that would

have catastrophic effects on populations and food supplies. We don’t yet

understand what this stuff does to living tissue, but it’s just a matter of

control. What do you think? This could be the way of the future.

The opinion you have about to this speculation

depends on your theory of human nature. No one can say what would happen in

this alternate reality, but my conclusion is that there is no leader now or

ever who would have supported this start-up. The likely response would have

been, “Spare me the science fiction nonsense, but tell me more about the

weapons.” As it was, the most Einstein ever said about making electricity from

nuclear energy was that it was “one hell of a way to boil water.”

Another interesting speculative question is

whether any nation would have built nuclear infrastructure if the implications

had been thoroughly discussed and put to a vote. The Manhattan Project was

carried out in secrecy under the leadership of General Leslie Groves, without

the knowledge of Congress, and $2 billion was spent on a massive system of

laboratories, mines, factories and enrichment facilities. The political leaders

didn’t understand the science or the health dangers, and the scientists naively

believed the bomb would be used to deter a Nazi nuclear attack. They were

shocked, shocked to realize that the $2-billion bomb would have to be used to

justify its cost and to make a show of strength to the Soviets.

The American public has always excused this Manhattan

Project secrecy as a necessity of the war, but nonetheless it was one massive

blank check that wasn’t really essential. The Americans quickly realized that

enormous generating stations and industrial plants were required, not to

mention access to lots of uranium ore, and the USSR, Germany and Japan all

lacked the prerequisites, under the conditions that existed from 1943-45.

America was the only country that had the capacity. By the spring of 1945,

Germany had surrendered and General Groves was worried that Japan would be done

too before “the gadget” was ready. The outcome of the war would not have been

much different without the bomb.

Few historians believe anymore that the atomic bombs were essential to end the war. There was no CNN in those days, so

most of Japan barely knew anything had happened. The generals in Tokyo

had heard only vague reports of a terrifying new kind of weapon, but they didn’t

know enough about it to be scared of it, and they certainly didn’t care about

the fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was just two more bombed out cities

after all the others that had been bombed by conventional methods.

After the Nagasaki bomb the generals still

wanted to fight on, and if they had had a chance to call a bluff and see if the

Americans would drop another one, they would have found out that there weren’t

any more. (The Bikini Islanders still had 11 months to enjoy their homeland

before the next bomb was ready for them.) The surrender happened only because

some cabinet members were able to get around the military leadership, sneak the

recording of the Emperor’s speech out of the palace, and get it on the radio. According

to historian Tsuyoshi

Hasegawa, what really

got the political leadership to surrender was the entry of the USSR into the

war in August 1945. They concluded, predictably, that going with the

capitalists would be the lesser of two evils.

As late as 1995 (and still now for a large

segment of the population), this was still a wild, revisionist theory in

America. A proposed

exhibit at the Smithsonian, commemorating the 50th. anniversary

of the atomic bombings, was to present a contextualized, multifaceted approach

to the interpretation of the history, but political opposition shut it down. It

was offensive to veterans to suggest that factors beside the bombs had an

influence in ending the war.

The standard defense is that the bombings were

justified because they eliminated the necessity of a land invasion in which

hundreds of thousands would die. Some even suggested there would have been a

million American casualties. The trouble with this reasoning is that it ignores

an obvious possibility: pack up and go home if you don’t want to invade. The

war was already over. Japan could no longer wage war outside its territories, it

could not have held on to Korea and Taiwan, and it was under blockade. The

threat of Soviet invasion would have made Japan come begging for an American

occupation, which is basically what really motivated the actual surrender.

Thus the atomic bombings were a sideshow, but a

nice demonstration of American power to usher in the post-war world. The entire

Manhattan Project seems like a series of events that spun out of control and went

beyond any outcome that anyone imagined at the outset. It expanded like as a

headless monster, and the mission creep has continued all the way to Fukushima and the present nuclear standoff with Iran.

| Colonel: What’s that you’ve got written on your helmet? Private Joker: ‘Born to Kill’, Sir. Colonel: You write ‘Born to Kill’ on your helmet and you wear a peace button. What’s that supposed to be, some sick joke?... Private Joker: I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, sir. Colonel: The what? Private Joker: The duality of man. You know – the Jungian thing, sir.

Stanley Kubrick (dir.) Full Metal Jacket. 1987

|

There are problems with speculating about how

things might have happened under different circumstances, but it is worthwhile

to run such thought experiments. I find it hard to believe that humanity would

have first tried to harness nuclear energy for anything other than weapons. The

struggle to establish renewable energy has shown that the fossil fuel paradigm

would not allow itself to be threatened by such a novel, risky and expensive

undertaking as nuclear power, which requires energy inputs from fossil fuels in any case. Using nuclear energy to produce electricity was a

side-benefit promoted to soften the criticism of the nuclear arms race and ease the conscience of the scientists who had contributed to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and it

was made affordable only by the pre-existing infrastructure for weapons. Once nuclear

power plants exist, they are all plutonium factories that add to the risk of

nuclear weapons proliferation and fill the world with nuclear waste for which

there is still no disposal solution. We could imagine a world with nuclear

weapons and no nuclear power plants, but not vice versa.

______________

The secret revealed in August 1945 shouldn't

be considered to have been a total a surprise at the time. News headlines from

1939-43 (below) told the world about the coming nuclear age, and a Scientific American issue from 1939 (excerpted below the table)

recounted the discovery of uranium fission by Otto Hahn in December, 1938. The

article explicitly describes the possibility of developing a new kind of

weaponry.

Articles about Uranium Fission

Reported in The New York Times before

Manhattan Project Censorship took hold completely:

·

Vast Energy Freed by Uranium Atom; Split, It Produces 2

'Cannonballs,' Each of 100,000,000 Electron Volts Hailed as Epoch Making, New

Process, Announced at Columbia, Uses Only 1-30 Volt to Liberate Big Force.

Jan. 31, 1939.

·

The Week in Science; When Uranium Splits Doubtful Source of Power

Cancer and X-Rays Neutron Possibilities News Notes. March 5, 1939.

·

Vision Earth Rocked by Isotope Blast; Scientists Say Bit of

Uranium Could Wreck New York. April 30, 1939.

·

Release Largest Store Known on Earth A ‘Philosopher’s Stone’ When

Separated in Pure Form It Can Yield 235 Billion Volts Per Atom of Its Own.

May 5, 1939.

·

New Key is Found to Atomic Energy; Actino-Uranium Is Credited With

Power to A Mixture of Physics and Fantasy. March 17, 1940.

· Vast Power Source in Atomic Energy Opened by

Science; Report on New Source of Power. May 5, 1940.

·

Third Way to Split Atom Is Found By Halving Uranium and Thorium;

Scientists at University of California Say Cleavage Creates Much Energy --

Tokyo Men Also Report Uranium Fission. March 3, 1941.

·

Scientist Reaches London; Dr. N.H.D. Bohr, Dane, Has a New Atomic

Blast Invention. October 9, 1943.

·

Research Institute is Seized in Denmark; Germans Are Expected to

Work on New Secret Weapon. December 12, 1943.

|

“These secondary neutrons constitute a fresh

supply of ‘bullets’ to produce new fissions. Thus we are faced with a vicious

circle, with one explosion setting off another, and energy being continuously

and cumulatively released. It is probable that a sufficiently large mass of

uranium would be explosive if its atoms once got well started dividing. As a

matter of fact, the scientists are pretty nervous over the dangerous forces

they are unleashing, and are hurriedly devising means to control them.

It may or may not be significant that, since

early spring, no accounts of research on nuclear fission have been heard from

Germany — not even from discoverer Hahn. It is not unlikely that the German

government, spotting a potentially powerful weapon of war, has imposed military

secrecy on all recent German investigations. A large concentration of isotope

235, subjected to neutron bombardment, might conceivably blow up all London or

Paris.”

Other sources:

“First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan; Missile Is Equal to 20,000 Tons of TNT; Truman Warns Foe of a ‘Rain of Ruin.’” The New York Times. August 6, 1945.

Philip Nobile (ed.). Judgment at the Smithsonian: The Uncensored Script of the Smithsonian’s 50th Anniversary Exhibit of the Enola Gay. Marlowe and Co.1995.The Pacific War Research Society. Japan’s Longest Day. Kodansha. 1968.

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2006.

Ward Wilson. “The Myth of Nuclear Necessity.” The New York Times. January 13, 2013.

from sources posted on Wikipedia: Debate over the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki:

After the war, Admiral Soemu Toyoda said, "I

believe the Russian participation in the war against Japan rather than the atom

bombs did more to hasten the surrender." (John Toland, The Rising Sun, Modern Library Paperback Edition, 2003,

p.807) Prime Minister Suzuki also declared that the entry of

the USSR into the war made "the continuance of the war impossible." (Edward Bunting, World War II Day by Day. Dorling Kindersley Limited, 2001, p.652) Upon

hearing news of the event from Foreign Minister Togo, Suzuki immediately said,

"Let us end the war", and agreed to finally convene an emergency

meeting of the Supreme Council with that aim. The official British history, The War Against

Japan, also writes the Soviet declaration of war "brought home to all

members of the Supreme Council the realization that the last hope of a

negotiated peace had gone and there was no alternative but to accept the Allied

terms sooner or later."

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete